Where Have the Amateurs Gone?

Two years ago, as an amateur trying to learn a craft and make a career out of it, I struggled. The experience left me unhappy and frustrated. Does it have to be so?

📣If this newsletter appears truncated in your inbox, please click on "View entire message" and you’ll be able to view the entire post in your email app.

In a 1993 The New Yorker profile, the late Ricky Jay, described by the writer Mark Singer as “perhaps the most gifted sleight-of-hand artist alive,” laid bare his misgivings:

People ask me why I don’t do lectures at magic conventions, and I say, ‘Because I’m still learning.’ Meanwhile, you’ve got people who have been doing magic for ten months and they are actually out there pontificating. It’s absurd.

It bothered Jay — who was an obsessive savant about everything that had anything to do with magic, sleight of hand, card tricks, conjuring, and other more arcane arts — that some magicians seemed to care precious little about the art.

T. A. Waters, a mentalist and someone who has seen Jay from close quarters, makes this observation, in the same The New Yorker profile:

Some magicians, once they learn how to do a trick without dropping the prop on their foot, go ahead and perform it in public. Ricky will work on a routine a couple of years before even showing anyone.

Jay didn’t have an ax to grind with practitioners making money off performance magic either. Over his career, he had on countless occasions shown the willingness to forgo substantial rewards when he had found his own sensibilities offended.

What was of import to him was the separation between what good magic looked like and what it felt like. To Jay, magic had to feel good in his — the magician’s — bones, before it passed muster for applause on the stage.

He would rather have had the company of hobbyists who had standards — the profile goes on to confirm that Jay’s “two most trusted magician confidants” were “world-class sleight-of-hand artists, and neither ever performs for pay” — than of professionals who didn’t.

Jay’s worldview instinctually struck a chord with me. There was something reassuring in holding on to the precept that good work always comes first. It felt right. I agreed in principle but what did my reality have to say?

This examination of my own experiences suggested to me that my actions may not stand up to Ricky Jay’s world view, which I was an advocate for. As much as I liked to believe that to bring to life work under-gestated is to subvert the creative process, the reality was that I was an online creator trying to balance learning a craft with making a business out of it.

If I had to continue down the path of an online creator, what should the mental model for my new career be? What did I need to understand about the pursuit of mastery and about making a business off it? What follows is the best answer I have been able to come up with so far.

My early experience as an amateur online

In 2022, I was selected, as one of two hundred, by LinkedIn India to be groomed and trained as a creator, as part of a nationwide incubator program.

I felt reassured by the validation. It whispered to me: You’re on a path. Follow it and you’ll not be lost. Being part of a curated cohort of creators made the assuagement all the more real.

I’m not a trained behavioral scientist or psychologist, just a self-taught DIY approximation of the same. In that capacity, and drawing upon my own experiences in corporate work — my then employer paid me for making Go / No Go recommendations on where to allocate money and men, and on occasions for incubating new business lines — I wrote about decision-making in white-collar work.

My day job was cushy but it didn’t make me jump out of bed. Was there anything out there that I loved, that didn’t feel like a job, that I could do for the long haul, I wondered. I didn’t know. When you’re not sure of a climb, there’s a comfort in climbing together. So, as part of this LinkedIn cohort, I tramped through the night and weekends, and any stretch of time beyond my day job, to try and change the trajectory of my professional life.

All two hundred of us in the LinkedIn program were first-generation creators. No one in their families had done what they were doing. But thanks to the internet, a number of them, especially the younger ones, had reference points in other storied creators and influencers. Those others who didn’t know better and had little social presence prior, like me, simply followed cues. One such signal was consistency. I quickly developed a posting cadence that felt natural the way it feels natural when everybody around you starts marching to the same beat.

I posted something every weekday morning. This was before the platform had any scheduling feature or allowed any third-party tools. My motivation aside, it was a hard regimen to keep up. At the time, I had a two-year-old to fit into my morning and she hadn’t received the memo. I also had predictable but non-fungible hours at my job. So, I had to wrap up my side gig before work. The time of posting seemed to matter a lot depending on the time zones of your audience, all of which made the process of writing and sharing within a narrow window a dance with too many limbs to mind.

The idea of writing down something to let it rust on the computer or in a private sanctum on the cloud felt like a colossal waste. If a post did well, it made sense to cash in. Find precisely what you did that clicked and replicate it, without falling into the trap of spamming. My interests were naturally wide, yet everyone I turned to said, Niche down! Stick to your game. I didn’t think I had a game yet but admitting that felt like it left me out in the open.

The pull of belonging to a fellowship is such that it can distort signals from the self.

As I toed the non-compulsory line, questions formed in my head. Why would anyone pay attention to me if I’m learning my craft and I’m putting out wishy-washy stuff? How can I come across as more confident? Sharing the minute you learn and teaching what you know is all good — but what if you’ve learned the wrong lesson? Should you not leave yourself space to change your mind before committing to it in public? Owning up to your full self is alright, but what about allowing yourself time to develop taste?

I answered them as well as one does without any new awareness. I found ways to justify what I wanted as my need: circumstances had given me the opportunity to make a mark as a creator and I had to use it. As I switched on the creator mode (literally) on the platform and started accruing followers, slowly and surely, the thought of creating for myself some sort of career optionality outside of my job as a corporate strategist took shape. I had no choice but to put the opportunity to use.

So, even when my experience of the journey confuted my expectations, I plowed on. When I didn’t enjoy the creator life, I told myself to stop acting privileged and try harder instead. You begin things that you give up midway, again and again, I told myself. Or, As soon as things get rough, you jump ship. If it was a form of self-manipulation, I lacked the wherewithal to notice it. I just told myself to chase what was ahead of me.

The default online

“Be so good they can’t ignore you” may pass off as Monday morning motivation, but it doesn’t pass muster for a credible default for online behavior. The biggest challenge for an amateur online is being found. Distribution.

During my apprenticeship as a creator, I found my focus shift from learning from the best sources, to sharing it with the right audience. Sharing is what helped me be found. I made choices that made it more likely for me to be discovered by others so that I could turn my knowledge into income over time. Holding such behavior in place was an entire structure in thought. Here are a few beliefs I held on to in my journey.

1️⃣Teaching is the best form of learning

Teach others what you know, to know what you think you know.

You start writing online by putting down scraps of what you know about something and then you make up the connective tissue that holds those bits together. This process extends to ways of creative expression beyond writing. Music, sketching, movies, podcasts, storytelling—sharing your work helps you get better at it. Besides, sharing online for an audience raises the stakes and compels you to learn by paying more attention. Making a mistake online can be a pretty good way of earning an education free of charge.

2️⃣Sharing helps you score gigs

What you put out online is a way to be found. The more bottles you put messages in and fling out into the digital sea, the better the chances of those bobbing bottles being found by others, who may be in need of exactly what you’re offering. They’re willing to trade their money and time for your knowledge.

Over time, as you build a reputation, sharing regularly shortens the funnel. Your next boss doesn’t have to read your resume because she already knows (and admires) your work. Your next client doesn’t need a discovery session because she has been to a masterclass you hosted last week. And so on.

3️⃣The world is changing so fast that no one is an expert, so don’t wait to be one

Dan Hockenmaier, Chief Strategy Officer at Faire, shares this hypothesis:

The signal that an MBA sends seems to be degrading, especially in tech. One driver is that the pace of technology is increasing so rapidly that it is just not possible to actually learn the latest things in a static 2-year program; it is more effective to learn continually over many years.

Your hard-earned laurels do not guarantee you a lifetime position; they are a ticket to bankruptcy if you just sit on them. In general, the shelf-life of expertise is shrinking. If you were an event organizer or taught in a classroom and you took a sabbatical just before COVID, you would return to discover that the world has moved on past much of your skillset. The future of work is combinatorial. Diverse skills increase the surface area of your relevance and open unexpected doors. So, keep turning what you learn into income without worrying about your credentials.

4️⃣Experts are not experts at explaining things

Essayist André Gide said, “Everything that needs to be said has already been said. But since no one was listening, everything must be said again.”

Reiteration matters because, until recently, it was the experts who did most of the talking and experts are great at talking with other experts while talking down to the rest. No doctor has enlightened a patient community and no architect has taught us how to build our dream house. They have the expert’s curse.

Furthermore, newer formats such as video offer much richer media to grab audience attention. Millennials and older generations are text-native, not video-native. As an amateur creator, you don’t need to say anything new as long as you lower the cognitive load on your audience.

5️⃣The path to quality goes via quantity

Austin Kleon in his book Show Your Work quotes this excerpt from David Bayles and Ted Orland’s book Art & Fear:

[A] ceramics teacher announced on opening day that he was dividing the class into two groups. All those on the left side of the studio, he said, would be graded solely on the quantity of work they produced, all those on the right solely on its quality. His procedure was simple: on the final day of class he would bring in his bathroom scales and weigh the work of the “quantity” group: fifty pound of pots rated an “A”, forty pounds a “B”, and so on. Those being graded on “quality”, however, needed to produce only one pot — albeit a perfect one — to get an “A”. Well, came grading time and a curious fact emerged: the works of highest quality were all produced by the group being graded for quantity. It seems that while the “quantity” group was busily churning out piles of work – and learning from their mistakes — the “quality” group had sat theorizing about perfection, and in the end had little more to show for their efforts than grandiose theories and a pile of dead clay.

“Done is better than perfection” as a maxim has a lot of legs online. Kleon suggests that you send out a daily dispatch of the work you’re doing. Every dispatch is an instance of iteration. The more the iterations, the better the chances of a magical mutation.

While these continue to be good reasons to show one’s work, none of them could explain why I felt that my online behavior had acquired the air of a performance or why I derived such little joy from my accomplishments online. Over time I surmised that my mileage varied because of a fundamental difference—that between learning online and learning.

Learning online and learning

I was late to join the social media bandwagon. When I did, in my thirties, after COVID, I used to scoff at “I got to seven figures in less than 6 months” or “This is how I gained 100,000 followers in 8 months.” I had never heard anyone say “Here’s how to master the cello in a year,” so such a flippant attitude toward time raised my eyebrows.

I should have dismissed these claims but I did not. Far from it. I started nibbling at them, then chomping on them. Before I knew it, these blasphemous ideas had taken shelter in me. My expectations had been distorted.

But this was not the only anomalous discovery I made on the path to gaining expertise online. As I understood the online game, play by play, I saw a new side to myself. There are a few proclivities that I uncovered down the road.

1️⃣ Expecting immediate results

In his book The Path of Least Resistance, structural thinker Robert Fritz divvies up the process of learning any new skill into three stages: germination, assimilation, completion.

The world is rife with possibilities when a seed is sown. That’s germination—full of the audacity of zero. Then comes the phase when despite all the watering and nurturing nothing seems to happen. Week after week, month after month, this may go on, leaving us wondering if our most cherished project is doomed. Except something is happening, just not for you to see. The plant is taking root, spreading itself inside the earth and grounding itself before it can sprout above the surface. Little surprise that this phase of assimilation can feel like screaming into a void. It bests many of us. We give up, not to return again. Our willingness to wait out this phase has been eroded by what we see around us.

Amateurs today hear the accolades for the work done by visionaries years ago — a kind of delayed applause — and they take that to expect the same at warp speed. Unable to see clearly when the cause and effect are separated by time, amateurs today are consumed with reverse-engineering success. They pin their hopes on a breakthrough of some sort, insisting that going viral or converting that one big client is a sign that one has arrived. Except that no breakthrough is permanent.

My journey as a creator specializing in decision-making is the first one to unfold almost exclusively online. Being outcome-obsessed has meant I have tended to think about things I have no control over — following, engagement, conversions — much more than before. The more I have measured my progress through these hard metrics, the worse off I have felt.

2️⃣Obsessed with finding a niche

Early in his career, conjurer Ricky Jay did stage appearances, performing in a bullfighter’s suit, with his hair slicked back and fake sideburns penciled out. He did a stage-illusion piece called “The Floating Cane” where he spoke no words and did his moves with theatrical flourishes. By his own account, such experiences “eventually made me realize I wanted to speak and I preferred close-up.” The experiments with ostentation brought him his own style. Jay developed and mastered stage patter, running against the grain of the biggest illusionists of previous eras who preferred to not be heard on stage.

In time, Jay came to be known for his signature style, described in The New Yorker as an “out-of-left-field brand of gonzo-hip comedy magic, a combination of [technical] chops and antic irreverence.”

Like the very best, Jay was happy to fiddle around for an artistic experience that felt intimately his own. No sooner than I had amassed a semblance of a following online, I felt a tug to cut down on the experimentation. The explore-exploit tradeoff seemed to swing toward cashing in on what was working. As the iterations reduced, the learning slowed down.

Finding one’s voice is an act of self-discovery. Finding one’s niche is an act of finding out who in the world thinks you’re interesting. Voice is brand identity; niche is market segment. Voice, inside out; niche, outside in. Hearing comments like “You have made such a strong niche recall for yourself” made me double down on the corner of the market I wanted without thinking about what felt most natural to me.

Jay’s style was honed by years of observation and reflection. His magic reflected his view of the world. I had no point of view I could call my own.

3️⃣Imitating

In René Girard’s writings on mimetic desire, built around the idea that human beings do not desire things immanently, a mediator guides the desires of others, often without them being fully aware of it. This is not all bad, I believe. Here’s an example from my life of mimetic desire helping the apprentice chart a new path:

Around 2009, in my late twenties, I quit my corporate job to write a book—a full-length novel in the literary fiction genre. There was a hitch. I had no experience writing fiction and had no business having these aspirations save a couple of encouraging appraisals from my high-school English teacher from a lifetime ago.

To remedy my tenderfoot status I took to reading the masters. I fed Arundhati Roy, Salman Rushdie (beautifully convoluted), Margaret Atwood (show, don’t tell), Ian McEwan and Alan Hollinghurst (so polished), Haruki Murakami, and Hilary Mantel (terribly underrated until her Cromwell trilogy) into my veins.

As I got down to write, I guilelessly reproduced what my senses absorbed. My writing style lurched, especially as I switched tutors, but I don’t remember ever being worried because the time I spent with the masters greased my writing process.

Anyway, most of the style-switching came to a stop once I met J.M. Coetzee. Writing about apartheid South Africa with a naturalistic flair, Coetzee hit the spot for me. It was like going to university. Before long, my writing showed traces of the same sparse style I was soaking up, and I was infusing in the protagonist of my book the same traits of a perennial outsider. By internalizing Coetzee, I was imitating him in the deepest way possible.

I completed my manuscript from start to finish in two years straight.

Here’s another example — dare I say a more common one — of mimetic desire robbing us of the pleasure of the process:

In 2022, when I was testing waters as a decision-making trainer online as part of the LinkedIn creator program, I came into the arc of several Girardian mediators—that is, influencers who were garnering the kind of attention I aspired to. Their posts had better reach, their accounts had a bigger following. I envied them, hoping one day to emulate them.

Faced with the prospect of decoding primary sources such as published research papers to explain why people were happier spending money on something unnecessary at a discounted price than on things they needed at fair prices, I took the easier route of browsing through TED Talks and YouTube bytes to reproduce content in overarching tones. Whom did I borrow this savoir-faire from? I took it from those around me who were doing well by piggybacking on more accessible content already summarized and packaged for consumption.

When Girard wrote “There is no question here of looking for the usual difference between copy and original for the very good reason that there is no original,” he might have been talking about social media. The mediator of an amateur is herself an amateur who too has borrowed.

With no authorized rulebook in the syllabus for online mastery or clear social norms on how to go about the process, I had no better plan than to copy others around me and through that process make the kind of splash they were making. Only I found that these influencers pushed the envelope in ways that made me queasy. Week on week, I vacillated between relief and despair.

Intuitively, it felt right to imitate those a step or two ahead of me so that I could continue to nudge forward the boundary of my developing abilities as a creator online, but my approach belittled this thing called taste. I did not develop taste the way studying the highest achievers in a field helps a greenhorn do.

I fought my instincts all the way through until I lost to them.

Without being guided by the work of the masters, how long would I have taken to finish my debut novel or whether I would have ever arrived at the coda is a counterfactual I cannot test out. Yet, I can surmise that had my foray into novel writing happened in the era of social media, I might have swapped the fulfilling but hard climb of longform fiction with the instant gratification of posting three times a day for a growing follower base.

4️⃣Passing off opinion as good judgment in a gatekeeper-less digital world

Here’s a grizzly Pulitzer-winning John McPhee reminiscing in Draft No. 4 about a callow McPhee, a good half-century younger and learning the ropes at The New Yorker:

The piece that changed my existence came two years later, and was a seventeen-thousand-word profile of Bill Bradley, who was a student at Princeton. Shawn edited the piece himself, as he routinely did with new writers of long fact, breaking them in, so to speak, but not exactly like a horse, more like a baseball mitt.

Shawn is Willian Shawn, the then editor at The New Yorker. More from McPhee:

For a week or so before the press date, we met each day and went through galleys from comma to comma, with an extra beat for a semicolon. One point he was careful to make several times was that he was not interested in buying pieces that “sound like The New Yorker.”

Gatekeepers like William Shawn performed necessary quality control that today’s permission-less economy sees as an unnecessary barrier. We scoff at the thought of appealing to the judgment of a handful of appointed custodians. “It’s just their opinion. Who cares?”

What separates an opinion from a considered judgment is a clear observation of reality. As the editor of The New Yorker for over two decades, Shawn read a lot of writing. We can barely see beyond the smog inside our filter bubbles, rarely hear beyond the echoes of our followers. There are few avenues for us to see good judgment in action.

Custodians do not just improve the quality of the product. We forget that these custodians hone the amateur’s craft, sharpen her judgment. In casting a critical eye, they separate the committed amateur from the disingenuous amateur.

Shawn’s daily sit-downs, though bruising, formed young McPhee as a writer of long fact. The success of the final piece impressed on him the value of a trained eye. McPhee gained not just in skill but also in humility. As my following grew online, I attracted more like me who agreed with more of what I put out and in this clamor of consensus, I heard few dissenting voices. I learned less with each iteration. But I was more confident that I was right all along.

5️⃣Fake it till you make it

I once held a “masterclass for emerging leaders” on team-building. As much as I knew that the spiel — masterclass for the more prosaic seminar and emerging leaders for the less flattering mid-level managers — obfuscated reality, I contributed to the murkiness.

A swift way of closing the breach between reality and the desired future is simply to pretend that the journey has been made. I was by no yardstick a master, even though I appropriated masterclass for the occasion, and emerging leaders seemed like a generous euphemism. Both the trainer and the audience were manifesting. In other words, faking it till we made it.

Trying to drum up self-confidence through manifestations and proclamations is an accepted form of self-propaganda. But the only sturdy foundation for confidence is to create the kind of results you want to see in the world. Push through the process all the way to completion. Not merely the results but also the confidence is yours for the taking. Confidence costs an arm and a leg when you want it and is expected without question when you have it.

Acting like a more confident version of yourself, even when you may not feel it, can help shape new beliefs about yourself. Simply pretending to know more than you do by assigning non-existent skills or status to yourself deceives others. The difference between the two is adopting the mindset of a lifelong learner so that you don’t see a gap between your current reality and desired destination as something to hide but something to bridge with purposeful effort.

If these are five of the most common online learner behaviors, what structure of thought and beliefs produces them time and again? And what is a solution — not symptomatic, but fundamental — to these manifestations?

Throat-clearing in public is not throat-clearing in private

“The way I think about taking on these arts,” says Josh Waitzkin, a polymath who has reached world-class levels in disciplines as disparate as chess, tai chi chuan, and Brazilian jiu jitsu and is now learning foiling, “it’s understanding what are the component parts and doing lots of reps in them so that you’re comfortable with them, then putting them all together. So my learning process won’t look great in the first couple of days or couple of weeks. And I’m not concerned about that.”

As an amateur in foiling surfing, Waitzkin talks about what he sees around him:

I think that one of the interesting parts of it, I think that a lot of what’s happening in surf culture and foil culture is people have these Instagram accounts, and they’re always posting videos of what they’re doing, and they have to look cool.

So there’s this groupthink that I observe around what looks cool, and what the micro-culture will approve of. So you can’t really do things outside of that. For example, putting on a helmet, putting on an impact vest, those things don’t look cool on Instagram. And so you can’t do those things if you’re going to be posting on Instagram every day, right?

As much as popular advice declares that you should share your process (and keep it authentic), the audience has no time for your throat-clearing. It wants you to hit a crisp note straightaway. Being caught out making a mistake in public triggers an automatic fight-or-flight response. It carries the purport of being banished from the tribe. This turns up the pressure on learners to cover up their flaws and present themselves as finished products.

We’re not so much frustrated by our art as we are by the comparison of it with the work of others, writes Amy Stewart, author of half a dozen bestsellers. In the early days of the accelerator program, LinkedIn pushed video in a big way to us creators. It organized masterclasses, got influencers to share editing tips, and boosted video content on the platform. Most creators in the cohort were unaccustomed to the camera. Goaded by the platform, they tried their hand at video. I too took a stab. Within weeks, the median level of video content had gone way up, fueled by the simultaneous urges of shining among peers and avoiding being the straggler. By the end of a couple of months, the video wave had petered out. Half the batch, including me, had given up on it; the other had upped its level in an escalating game of showmanship. It’s been more than two years since and despite my best efforts I’ve published only a handful of video posts, as I continue to be self-conscious before the camera. I would rather not try the game than try and suck at it.

Social media is not the bustling coffee shop or street corner where people of varied interests and dispositions meet to return richer unto themselves, as perhaps it said on the label. It is a stage where amateurs meet and do their thing while auditioning to become the next sensation. They both conceal and sharpen their quirks and foibles in the service of a performance. Today’s digital amateurs approach their actions with calculated intent. I know a bit about it because for a time I tried to do the same. And failed.

Focusing all energy on what you don’t want

Amateurs who are hungry for swift validation are particularly susceptible to the strategy of doing something to get away from something else painful. Avoiding immediate pain or ennui feels so necessary they don’t know what they are trading it for. Call this the strategy of avoidance.

Prior to my online apprenticeship, I was in a senior position with a steady job that paid my dues and bought me nice dinners from time to time. The company had gone remote after COVID, so I saved abundant time and energy by avoiding a commute through Mumbai traffic. All of which should have lulled me into maintaining the status quo. But I wasn’t satisfied with just stumbling out of bed every morning. I wanted a reason to leap out.

The LinkedIn program offered promise. I liked unscrambling business decision-making and enjoyed the process of writing about it. Unlike a number of other creators, if not most, in the program, I had the safety net of a day job. That alone should have propelled me to do it my own way without worrying about slipping up. But I was, or grew over time, too afraid of being stuck in a purposeless job. Too desperate for shelter albeit on a new career path. Too eager to move from one life situation to another. All because I felt I had no choice. I had to do it.

Robert Fritz, structural thinker and author of several books on how to change your behavior by changing the structure of your life, writes:

A real choice means we can do it (whatever the it is) or not. If you must do it, you have no choice. Some people use the word “choice,” but they don’t really mean you can do it or not. Sometimes they think that a choice is forced upon you, and if you don’t do whatever the it is, you will pay a price until you wise up, and finally make “the right choice.”

When we feel we must do things and these must-do things go bad, be it managing weight or switching careers, it is hard to take responsibility for the consequences. Because we don’t believe we have made a choice. The choice, if at all, has been thrust on us, and so have the consequences. Neither of them are ours. It feels like an out-of-body experience we have no control over. It felt like that for me.

Fear, guilt, and escalating inner conflict — these are standard side-effects when we do things as part of this avoidance strategy. Like many others, what I was running away from was more important to me than what I wanted to run to. Only, my head was foggy about where it wanted my feet to go. I had no destination I had chosen for myself.

Confusing means for ends

It is common to have amateurs online talk about, in response to the question of what they want, not the end result but the means to that end.

I want to retire at forty. I want to sell a thousand-dollar course. I want my podcast to have a million downloads.

Ask them if this is a step towards some other, bigger result and they may look puzzled. “What do you mean? This is what I’ve been working toward for the last year.”

When Ricky Jay was writing his magic masterpiece Learned Pigs & Fireproof Women out of a library, the librarian, an English professor himself, persuaded Jay to apply for a postdoctoral fellowship. When Jay said he didn’t have a doctorate, his kind interlocutor suggested a master’s degree. When Jay clarified he didn’t even hold a bachelor’s degree, the librarian simply remarked, “Well, you know, Ricky, a Ph.D. is just a sign of docility.”

Jay went to five different colleges over a period of ten years, ultimately not graduating. When Jay was not switching colleges, he learned by hanging out of the pockets of the best up-close sleight-of-hand artists at the time, such as Dai Vernon and Charlie Miller.

Ricky Jay was dead serious about his education, just not about paper credentials. He wanted to master the craft of magic. That was his only end, and to that end he pursued whatever means felt right to him. He switched colleges when they couldn’t take him closer to mastery in magic.

In a choice between means and ends, it is always the means that are fungible.

In much of the advice on putting our work out online, sharing what we’re good at qualifies as a means to a bigger end: money, job, career, speaking gigs, early retirement. The conversation too often ends here. It shouldn’t. A month after retiring at forty you may experience an ego death. Or after taking your podcast to a million downloads, you may be so tired you may not want to set another goal like that again.

Dig deeper here and you may find that retirement or downloads are in itself not the finish line. They are mere step-stools to something more. Perhaps a compelling vision. Not being curious about such a vision drains achievements of meaning because you haven’t accomplished the thing you truly want that you haven’t yet found the language to express.

I was guilty of the same. I did not know what I desired in and of itself. I did not have a clear vision that was true for me independent of circumstances. Without a vision to anchor my life’s pursuit to, I was just bobbing in the ocean of circumstances.

I did not know what I wanted to become.

Gregory Mendel cared for what he did

Gregory Mendel had only ever had one career: as a monk. Biology books today may invoke him for his contributions to decoding heredity, but taking purebred pea plants and crossing them was only a side gig.

Mendel conducted thousands of experiments making hybrids, and then hybrids of hybrids, of peas. Peas self-fertilize, so to make them cross-fertilize, Mendel had to first neuter each flower and then take the pollen from one flower to another. This would be back-breaking work for any research team today, and Mendel worked alone on a plot of land given to him in the monastery.

Siddhartha Mukherjee writes in The Gene:

Between 1857 and 1864, Mendel shelled bushel upon bushel of peas, compulsively tabulating the results for each hybrid cross.

[....]

The small patch of land in the monastery garden produced an overwhelming amount of data to analyze–twenty-eight thousand plants, forty thousand flowers, and nearly four hundred thousand seeds. “It requires indeed some courage to undertake a labor of such far-reaching extent,” Mendel would write later.

In 1865, eight years after he began producing hybrids, Mendel presented his findings to an audience at the Natural Science Society in Brno. Later, his paper was published in the annual Proceedings of the Brno Natural Science Society. Mendel asked for forty reprints, of which by fair estimation he sent one to Darwin who didn’t reply. By the end of 1866, Mendel was writing to Carl von Nägeli, a leading botanist of the time who “had an instinctual distrust of amateur scientists.” After some delay, Nägeli sent back an offhanded “only empirical… cannot be proved rational” to the amateur gardener Mendel, instituting an arbitrary distinction between experimentally deduced conclusions and those arrived at by employing reason.

For the next seven years, Mendel wrote several more letters to Nägeli that “took an almost ardent, desperate turn” while Nägeli “remained cautious and dismissive, often curt.” Mukherjee notes:

The possibility that Mendel had deduced a fundamental natural rule—a dangerous law—by tabulating pea hybrids seemed absurd and far-fetched to Nägeli.

Mendel passed in 1884, leaving all his deductions to the world in one seminal yet obscure paper. Until 1900, unaware of Mendel’s work, three other scientists — the Dutch botanist Hugo de Vries, the German botanist Carl Correns, and the Austrian botanist Erich von Tschermak-Seysenegg — were replicating Mendel’s experiments without realizing so. Each of them in due time would rediscover the amateur Mendel’s ideas about heredity and, in some cases, be forced to credit the deceased hobbyist gardener.

In his last letter to Nägeli in 1873, sixteen years after he started dabbling in plant studies and soon after he had been promoted to the position of abbot and throttled with paperwork, Mendel wrote, “I feel truly unhappy that I have to neglect my plants… so completely.”

Recounting Mendel’s efforts to press on even as he was continuously relegated to the footnote of his times, Mukherjee opines that courage is the wrong word to describe the amateur botanist’s undertaking. I agree. So what urged Mendel?

I would call it a feeling of care.

The problem with Ikigai is that the world will always be hungry for beauty

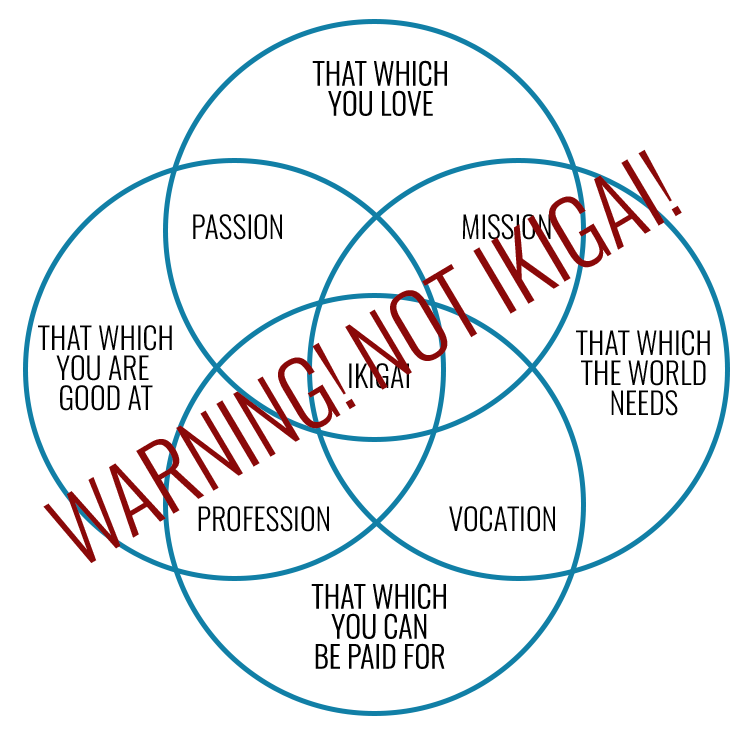

Start with a demand in the market, I got counseled by friends and well-wishers when I first started voicing my desire to quit my corporate job to do things I was energized by. Do you know about Ikigai, they asked in the manner of showing me a path? I checked online. Finding one’s Ikigai was arriving at the center of four circles:

– Are you doing something that you love?

– That the world needs?

– That you are good at?

– And that you can be paid for?

I felt queasy about tying my happiness to something outside of me—what the world needs and what it was willing to pay me for. But having already exhausted my savings once in my twenties, I was determined to be worldly-wise this time round. So I put my head down and searched for answers to the four questions. The unease didn’t go away. I tried to ignore it and get on with things. Until earlier this year, I came across the story of David Brower.

David Brower was one of the most influential conservationists of the twentieth century.

In 1960, Brower, then President of the Sierra Club, founded the Sierra Club Books. The publishing division, under his personal supervision, put out its first collection of landscape photographs of the highest resolution accompanied by snippets of moving prose.

To say that a bunch of coffee-table books changed the course of wilderness conservation in America may sound outlandish until you consider that in less than a decade, the Exhibit-Format imprint had amassed ten million dollars from the paying public. At twenty-five dollars a copy, the books cost an arm and a leg for the time but people lapped them up because they were brilliant. They were, as narrated in Encounters of the Archdruid, “big, four-pound creamily beautiful, living-room-furniture books” containing writings of premier naturalist writers like Henry Thoreau and John Muir.

What did Brower see that convinced him that the world needed exorbitant coffee-table books on wilderness preservation? Nothing. No one could have predicted their success. The books sold because they were beautiful. People parted with their hard-earned money because they cared for beauty. So, what about Ikigai? Where does it fit?

An admission from blogger Marc Winn is in order:

In 2014, I wrote a blog post on the subject of Ikigai. In that blog post, I merged two concepts to create something new. Essentially, I merged a venn diagram on ‘purpose’ with Dan Buettner’s Ikigai concept, in relation to living to be more than 100. The sum total of my effort was that I changed one word on a diagram and shared a ‘new’ meme with the world.

Since then, public response to that meme got out of hand. Several books have been written on it, documentaries commissioned, online courses created, and it has been discussed in publications all over the world. The World Economic Forum have even spoken about it. Not a week goes by that I don’t see the diagram being shared by someone of high profile.

Winn’s visualization of Ikigai was his own interpretation. It was nothing that the Spanish author and psychological astrologer, Andres Zuzunaga, who created it in 2011, had signed off on. We know this because atypical of social media, Winn posted a follow-up clarification years after his original reinterpretation.

What is Ikigai, again? Here’s a 1999 definition closer to the original Japanese way, attributed to Noriyuki Nakanishi:

The word ‘ikigai’ is usually used to indicate the source of value in one’s life or the things that make one’s life worthwhile. Ikigai gives individuals a sense of a life worth living. It is not necessarily related to economic status.

As a beginner practitioner, my thoughts endlessly circled around what niche to crack, what was in demand, and so on. So much energy directed at elements beyond my control, and so much misery.

Good art has its own way of justifying its existence. Over this year, especially since I’ve quit my corporate job, I’ve come to realize that if you care about what you do and if your highest level of fulfillment is to create good art, your work will find its audience. My learning could just exist for my satisfaction first. It is perhaps presumptuous to consider what the world needs; what matters is the beauty you can bring to the world. Ikigai is no problem for me. I know that the world will always be hungry for beauty.

Unless I give myself a break from slapping big plans on a young exploration, I cannot make room for passion and skill to grow. A reason to get up in the morning need not be grand. It need not be justifiable. It just needs to be mine. I must choose it.

A final tale

In 1984, as the Mulholland Library of Conjuring and Allied Arts was being put up for sale, Ricky Jay was asked to assume the position of its curator and help catalog the collection as well as advise the sellers on its distribution should the collection be broken up and sold to multiple buyers.

Anybody who knew Jay knew that he was as obsessed with the practice of magic as he was with its study. If the chance to catalog the foremost collection of “printed materials and artifacts related to magic and other unusual performing arts” was a lucky break for Jay, it soon turned into a wet dream when Carl Rheuben, a banker who bought the entire collection for $575,000, employed Jay to oversee the acquisition with no strings attached while simultaneously offering him a small theater where he and other artists compatible with his attunement could perform when they wished to.

Jay lived his dream for the next half a dozen years until the Californian regulators closed down the bank Carl Rheuben owned and Rheuben himself filed for bankruptcy. After more than a year of feet-dragging, the regulators finally put the library and Jay’s future up for grabs at an auction. Between the collection’s first and second auctions, under Jay’s custodianship, the Mulholland Library had appreciated considerably in value.

At the auction, David Copperfield, the most ornate of performance artists who orchestrated stage illusions with the fanfare of world heavyweight boxing showdowns and had no idea of or interest in the contents of the collection, made an offer. Copperfield bought the Mulholland Library unchallenged for $2.2 million. After an undisclosed span of time, Copperfield had Jay flown into Las Vegas, the new home for the collection, to make an offer to the lesser known magician. As recounted in Jay’s The New Yorker profile, this is what happened next:

A driver met Jay at the airport and delivered him to a warehouse. In front was an enormous neon sign advertising bras and girdles. It was Copperfield’s conceit that the ideal way for a visitor to view the Mulholland Library would be to pass first through a storefront filled with lingerie-clad mannequins and display cases of intimate feminine apparel.

[....]

When Copperfield pressed one of the red-nippled breasts of a nude mannequin, the electronic lock on a mirrored door deactivated, and he and Jay stepped into the main warehouse space. Construction work had recently been completed on an upper level. Jay followed Copperfield up a stairway and into a suite of rooms that included several offices, a bedroom, and a marble-tiled bathroom. The bathroom had two doors, one of which led to an unpartitioned expanse where the contents of the Mulholland Library — much of it shelved exactly as it had been in Century City, some of it on tables, some of it not yet unpacked — had been deposited.

By the end of the hour, which is as long as he stayed back, Jay had seen enough to frame a clear response to Copperfield’s lucrative offer of becoming a consultant for this new avatar of the magic world’s most treasured collection.

Even when he was jobless, collection-less, and theater-less, Ricky Jay was not conflicted between what he truly wanted in life and how he was comfortable getting it.

What separated Ricky Jay, who refused pots of easy money all his life, from those who used his brilliance to make easy money; what separated David Brower, who once upon not liking the look of a batch of picture proofs had ten-thousand dollars’ worth of plates chucked out, from the average publisher of conservationist writing; and what separated Mendel, who spent eight years shelling bushel upon bushel of corn, from the garden-variety hobbyist gardener. Ultimately, what separates good art from bad art?

A feeling of care.

I got a lot of well-meaning advice on what I should do and what I should care about. I should have a call to action to direct people to, I should do more videos, I should break down one piece of content into bite sizes across platforms and formats. I tried putting into practice most of this counsel. None stuck on.

It wasn’t me. I disliked the experience. In sifting through the many hacks and strategies that I could apply for tangible gain, I forgot to check how they tracked to who I was. I wanted to be many things, depending on whom I was being shaped by. But who I wanted to be for myself wasn’t coming through.

In real life, we acquire the fear of failure with success. As our digital avatars, we don’t even have to wait for coveted success to begin to fear failure. Since amateurs online already are impersonating their idealized versions, they have caught on the fear of failure without even tasting true success.

Since I’ve left a corporate career earlier this year, I have given up trying to make it. Once I have let go, slowly, the pressure of achieving things has loosened its grip on me. I’m in less of a hurry. I’m able to get out of my own head. I’m opening my life to beyond my filter bubble.

Through this process, the most meaningful goals I have arrived at for myself are different from what I had imagined before. I no longer want to be a CXO, or make money and retire at fifty, or be an influencer. None call out to me in the clear light of the realization of who I am.

I want to do work that feels like play. I want to write and I do not want to retire. I want to help people reach their highest potential in ways I find energizing. I care about all these things.

🙏Many thanks to Rohan Banerjee for his edits, thoughtful suggestions, and company over coffee.

I learnt so much from this piece, and discussing it with you. Still in awe of your longform writing prowess!

I want to do work that feels like play.

What a beautiful writeup, so much to absorb here. A lot of hard and difficult to admit truths told with a genuine humility. Thanks Rout!